An anthropological perspective on human beauty

Charles Darwin marveled: “The peacock with his long train is more like a dandy than a warrior.” This expert observer was fascinated by beauty in the animal kingdom because it seemed to present an evolutionary puzzle. To produce ornaments with no function the body squanders energy that could otherwise be used for survival. Beauty is biologically ‘expensive’. The fact that it is prevalent across the natural world shows that it is deeply rooted in animal evolution, from the optic nerve that recognizes it to the courtship rituals where it is spectacularly displayed.

And what of humans? We too are exquisitely sensitive to beauty. Consider the energistic metaphors often used to describe it: ‘radiant’, ‘dazzling’, or more recently, ‘hot’. Smiles are said to ‘light up’ rooms. Many coming of age rituals – regardless of whatever social meaning they express – are also joyous celebrations of the beautiful body. The classical world was even concerned that crossing paths with a beautiful person would imperil the observer, philosopher Elaine Scarry points out. Plato describes a man who after beholding a youth begins to spin, shudder, shiver, and sweat. The animal inheritance of beauty in us partly explains why the glimpse of beauty can generate such a strong affective response.

Human beauty, though, is experienced and expressed within culture. We are the symbol-making animal. And the body is our canvas. The anthropological record shows that nearly everywhere we have painted, cut, and molded the body. These enormously inventive techniques have not only shaped the body, but instructed us how to see beauty. The Azawagh Arabs of the Western Sahara learned to love the rolls of flesh on women fattened on pap (maize porridge). Eighteenth century Europeans were moved by the bulge of the male calf. The Japanese became connoisseurs of a part of the body neglected elsewhere: the nape. Through our life in a group, we come to know the beautiful body.

While the tremendously seductive photographs of the global fashion industry have oriented our experience of beauty towards the still image, beauty is often experienced as a living quality of the body in motion. Societies have developed a vast range of body techniques: arts of movement, training, and performance. The body engaged in activity – walking, dancing, loving, playing, competing, fighting – is not only social but often beautiful too. Beauty is not a static quality, but is revealed in motion: a smile, a toss of the head, a display of grace.

We may think of the body as a kind of property, something the individual has. Anthropology suggests a different perspective: the efforts of the group make the body beautiful and healthy. In Fiji, the weight and attractiveness of the body is seen less as a matter of individual discipline and more as sign of collective nurturance, anthropologist Anne Becker has shown. Beauty and health depend on daily efforts that require working together, love, and care.

The knowledge of the body that develops through care in small groups can even provide some protection against a scourge of the contemporary world: body alienation, or when the body becomes a burden or source of shame. In Belize, for example, anthropologist Eileen Anderson-Fye has shown that local beauty standards favor a “Coca-Cola” or “Fanta” shape in women, the local idiom for a curvaceous figure. This bodily ideal persists despite the prevalence of glamorous images of thinner bodies in media, and few women develop extreme distress about body size. A distinct folk psychology – expressed in the phrase “never leave yourself” – helps protect women from obsessive weight concern and eating disorders. Transmitted by intimates to younger girls, this ethos centers on self-care and self-affirmation.

Beauty is not only made by social relationships, it generates new ones.

Closely related to charisma, attractiveness often seems to short-circuit other networks of power. In many societies, from feudal Japan’s Tales of Genji to modern Brazil’s telenovelas, beauty has been depicted as the source of passions that transcend established hierarchies of rank or status. Attractions can bond individuals across seemingly sharp divisions between human groups, from Romeo and Juliet to Mildred and Richard Loving (two Americans who defied draconian laws outlawing interracial marriage).

In the natural world, evolutionary processes generate aesthetic transformation. Humans, though, apply the powers of their will and imagination to the pursuit of beauty. The Romantic movement put forward the alluring idea that one’s life can be made into a work of art. This dream is often applied in the contemporary world to the body itself. Health becomes a qualitative state of well-being, rather than the mere absence of disease. Many body practices aim at an “art of health” created by both patient and healer throughout the life course. The human body becomes not just an object of change, but the seat of experience and the vehicle of its own aesthetic transformation.

Alexander Edmonds is an anthropologist who has researched the cultural dimensions of the body and beauty. This essay is excerpted from his publications, Fleshly Beauty, Beauty and Health, and Body Image in Non-Western Societies.

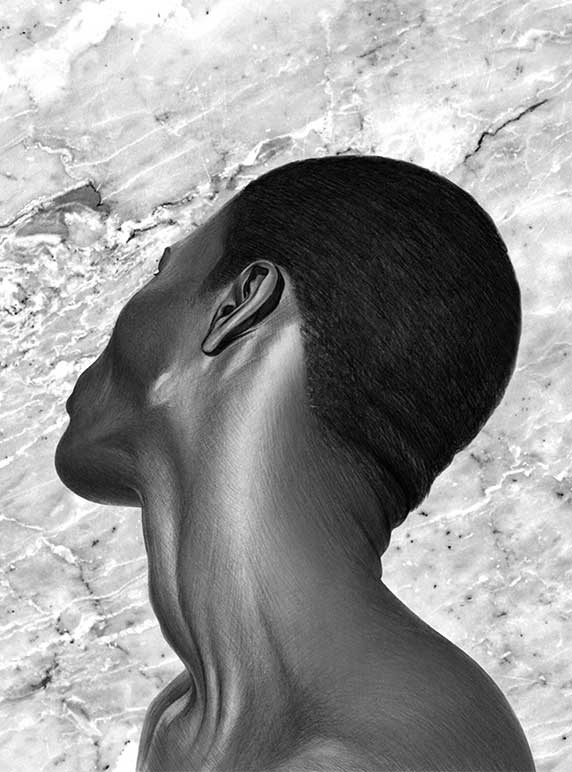

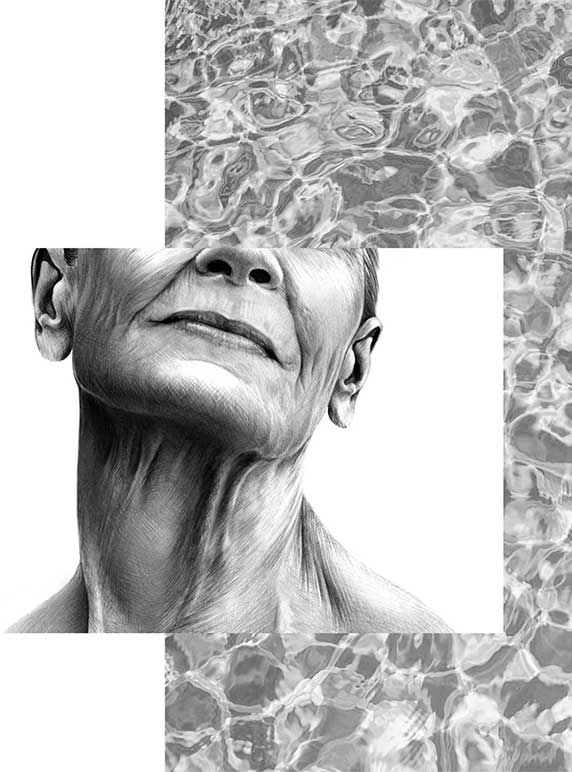

Image/illustration Credit:

Aiste Stancikaite is a Lithuanian born artist based in Berlin. Her work often pairs precise pencil drawings with abstract uses of both digital and traditional mediums, to create images with a focus on detail and texture.